Muleteer… Vaquero… Priest… Independence Leader

Prefer to listen to the story of Jose Maria Morelos?

Introduction

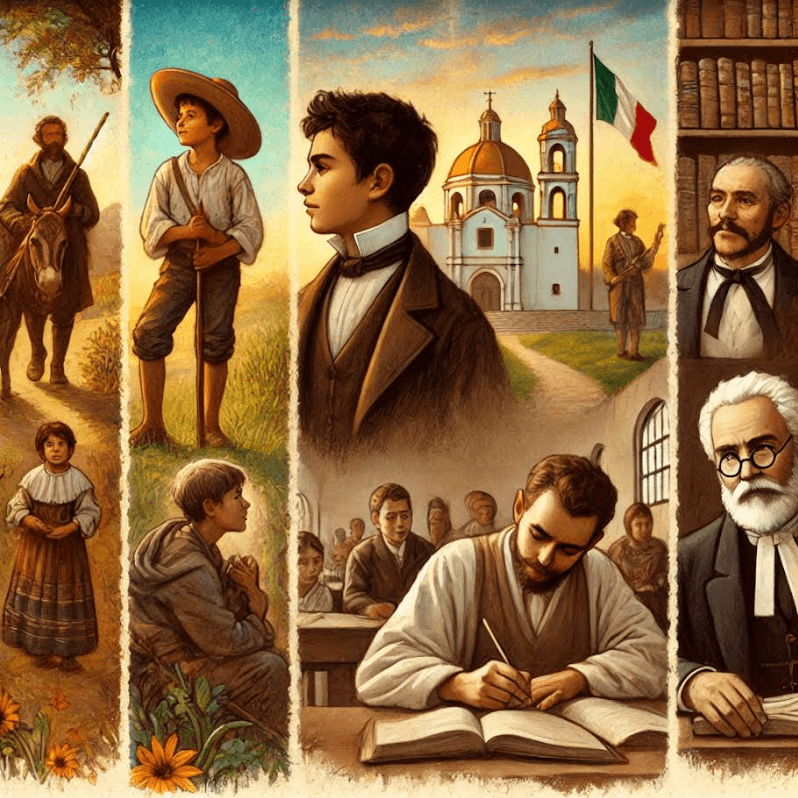

Jose Maria Morelos was born of parents mulatto and mestizo, into a society in which one’s entire future was measured out by blood proportions, ethnic history, and skin tone. 18th-century Mexico, or “New Spain,” as the Spanish peninsulares preferred, was obsessed with class, caste, and classifications based upon blood, birthplace, and ethnicity. Among pure breeds, Morelos was a mutt. In other words, he was seriously disadvantaged, more than either of his parents, before he was even born. And yet, the name Jose Maria Morelos is carved in the Mount of the Immortals, Beloved Forever, a Hero of Independence in Mexico. The names of the others are forgotten.

Chapter 1. Hello Jose Maria

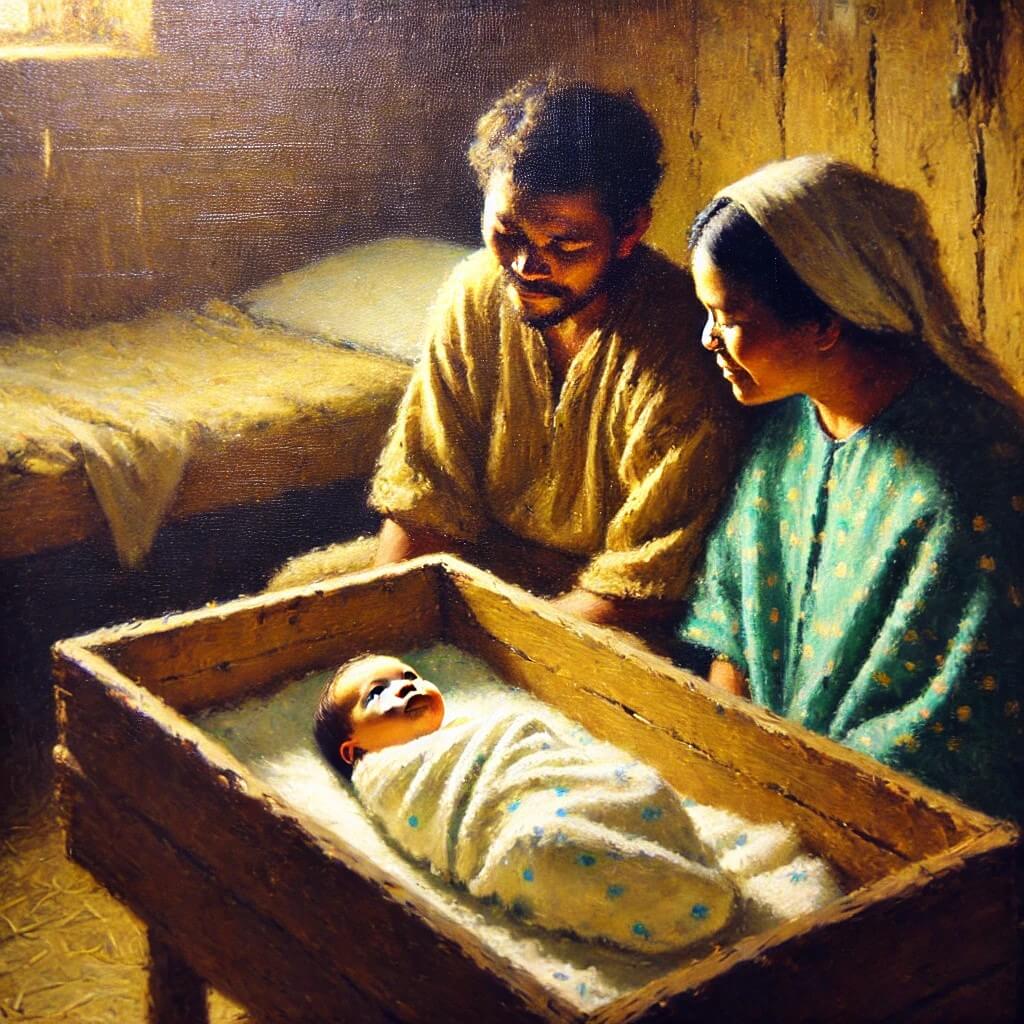

The little baby was born September 30, 1765, into the world of the poor. To outsiders, the scene may have been, almost, Dickensian, a portrait of poverty; mother, father, she, the mulatto freed slave, he, the mestizo wage-earning carpenter, both clothed in garments years past the time others would have discarded them, huddling, over, a box confiscated from the barn containing, their baby. It’s a story we know well. We have data and statistics, charts, and diagrams. Experts have developed models and provided projections, and we can be pretty sure that the rest of the story includes a mother’s tears, a father’s humiliation, a son’s hardship, and then, the end, a tidy end.

But who can say what really passed between those parents and the infant in that scene? The insiders are no longer with us, and all we have as evidence in this 21st century are these monuments, lots of them, monuments all over the place, some over a hundred feet tall. Perhaps, those parents looked upon their infant in wonder, and in the joy of family love, the awareness of their poverty disappeared in irrelevance. Giggling, one, picking up the thread of an ongoing conversation, suggests, “Jose Maria,” and then, “Why Not?” The other, laughing, says, “But”, and grins, blushing. The little one, looking up, incapable of anything other than belief, locks eyes with Mama, and then Papa. They knew the beauty of this scene. And so, papa Jose Manuel and mama Joanna Maria agreed. His name shall be Jose Maria Morelos. And so they named him after the parents of the best hope they knew, not Joseph, not Mary, but Joseph and Mary. And then, in the sing-song voice that every parent knows, they looked upon this tiny human being and said, “Hello, Jose Maria.”

Chapter 2. The Muleteer

History next records that he was a muleteer, a task often given to boys when they became somewhere around ten years old. And so Jose Maria entered into the hearty outdoor life of the working-class poor. He couldn’t know, of course, that lessons learned behind that mule would prepare him to general Mexico’s War of Independence; he just knew that Mama and Papa said it was important that he do this work and that it was good work and that they encouraged him, and advised him, to a job well done.

“Remember,” they’d remind him, “It is the mule who is doing the work, so respect him and his strength and make sure he has the food and water he needs.” “Mules are as different from one another as people,” they’d say, “so be kind.” “To plow a straight line, keep your attention fixed on your goal, the end of the row, not your feet or the mule’s feet.” “A well-trained mule makes the plowman’s job easier.” “A horse may be faster and flashier, but a mule is stronger and more precise for plowing.” And so he learned from the mules how to get things done, from dawn till dusk, year after year, until the opportunity arose to become a cowhand.

Chapter 3. The Vacquero

Cowhands in Mexico were known as vaqueros; vaca, of course, being Spanish for “cow.” Vaqueros were the original cowboys of America, with legendary skills that have inspired countless movies. It was the vaqueros who taught their northern trade brethren in Texas, and Colorado, and Montana, how to move a herd, how to cut cows from that herd, and how to rope a stray at full gallop. Long hours in the saddle in hard environments shaped a vaquero into a formidable being; independent, capable, empathetic, and, when needed, dangerous. Routinely living off the land for months at a time, the vaquero would deliver newborn calves, nurse the injured, and rain fire and fury on predators, be they man or beast. The sight and sound of vaqueros flying down the mountainside, screaming with ropes reeling and whips cracking, was like thunderbolts from the angry gods. It was the vaqueros who would provide the muscle for the army that won Mexico’s independence. Morelos would have been about 14 or 15 years old when he was noticed and brought on to a ranch as a helper to the vaqueros, about the same time Nature was equipping him with the physique he’d be needing.

He’d have started with simple tasks, helping the vaqueros with their saddles and ropes, feeding and watching their horses, joining the vaqueros in the night watches, singing to keep the herd calm. And then he’d learn to make his own ropes, and to use them; and he’d learn to ride, and to train horses, the vaquero way. And, as he learned to ride, he’d be given the job of watching for stragglers, following the herd, riding in the rear, eating their dust all day long. And then one day the lead vaquero yells out, “Hey Vaquero, Go get that cow!” and you, the helper, were the nearest. You perform, expertly cutting through the brush this way, heading off the calf that way, and bringing him home to safety. That evening, around the fire, a vaquero singing in the distance, everyone laughing, and no one needs say a thing; everyone saw it and knew it; you’d become a vaquero. And so he learned that the open range doesn’t care if you are mulatto or European, mestizo or indios. All that mattered was getting the job done. And there, he made lifelong friends.

Jose Maria thrived on the range and saw others thrive too. Mestizos, reserved in town around the gachupines, emerged boisterous, colorful, and capable on the range, where respect earned was freely given. Caste and color made no difference. Years later, when the opportunity would arise for Morelos to provide guidance for an emerging independent society, he would do so in a document entitled “The Sentiments of a Nation”; and in words which may remind us of Martin Luther King, a century and a half later, Morelos would say, “May slavery be banished forever, together with the distinction between castes, all remaining equal, so Americans may only be distinguished by vice or virtue.” Some believe the title is better translated as “Feelings” of a Nation, as though Morelos was attempting to capture his own feelings and to implant them into the soul of his people, that the coming independent country would become a nation truly feeling the bonds of mutual respect.

It may be considered an indicator of the respect and friendship he experienced that, twenty years later, when he called upon the people to form an army, many rallied to him with little question.

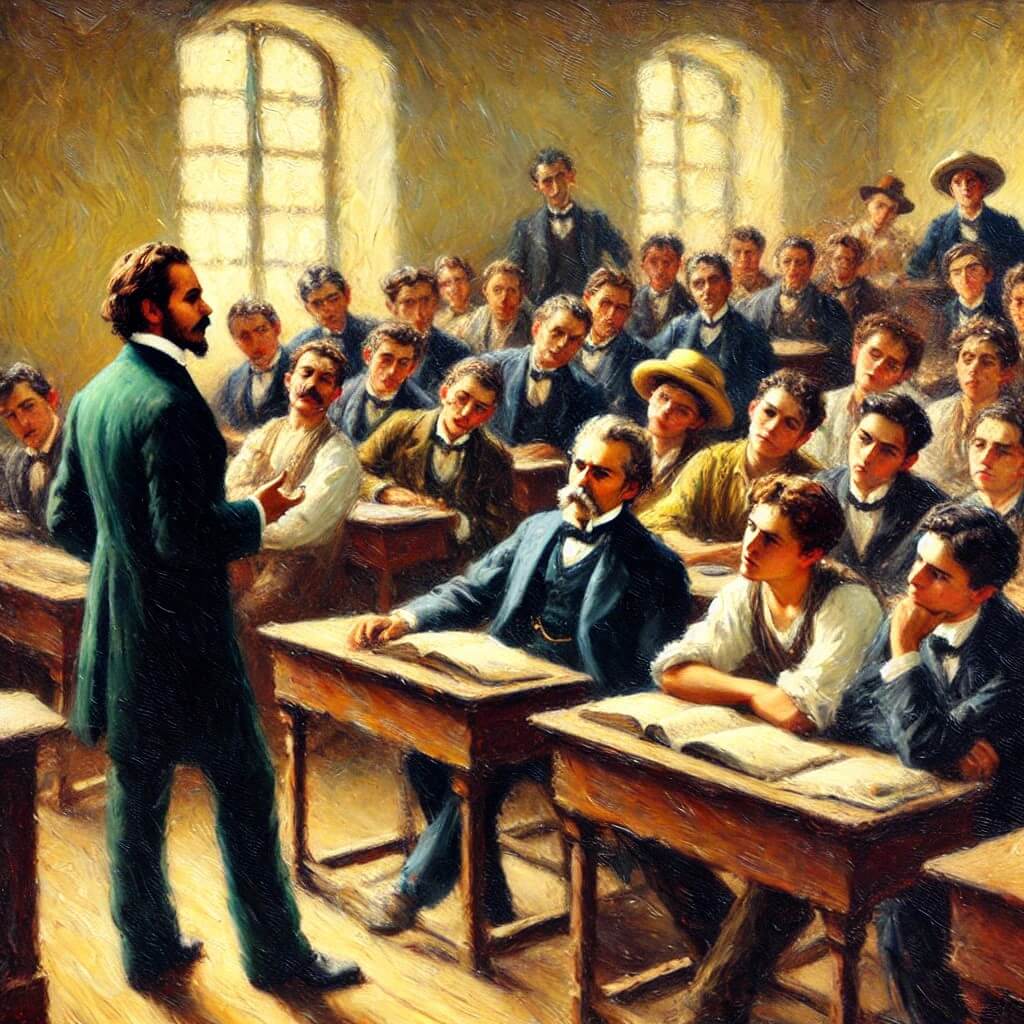

Chapter 4. The Student

By all reports, young Jose Maria had loved school. But the growing family had some problems, as families do, and those problems led to financial problems, as they too often do; and young Jose Maria began to go less and less to school and more and more to work. Then his father died, and Jose Maria became the main provider for his mother and sister; and school became an unfinished memory.

But through the years, as muleteer and then vaquero, the love of learning never died. Perhaps it reminded him of his early childhood with his family intact; perhaps it merged with his desire to make his mother proud; we don’t know, but we do know that he determinedly saved up some money, and, at age 25, with encouragement from his mother and sister, the seasoned cowhand enrolled in San Nicolás College in Valladolid. From reports of his professors, he seized upon his studies as enthusiastically as any 10-year-old schoolboy.

There Jose Maria resumed his studies of Latin and History. Then he advanced to Rhetoric and Theology, and then, next, to Philosophy; and it was there, in all likelihood, he encountered Hidalgo. Miguel Hidalgo, who would become known as the Father of Mexico, whose ringing of the church bells of Dolores would be remembered as a founding act of Mexican Independence, was steeped in the literature of the Enlightenment and was rector of the college at Valladolid. As a teacher, he was as bold as he was brilliant. He had little use for the doctrine of the divine right of kings and not much more for the authority of popes. But he was luminescent with the literature of the enlightenment, holding forth on the rights of man, the blessings of legal restraints to government, and expansive on the dignity of humanity. “All men a created equal,” Hidalgo read to them, “endowed by their Creator with unalienable rights,” Hidalgo taught them. And he reminded his students of what was happening in the United States just North of them; France across the Atlantic, and Haiti to the East.

It must have been wonderful, Jose Maria’s feelings, as he listened to Hidalgo. His experiences were affirmed, his intuitions confirmed, and his confidence soared as the mighty intellects of The Enlightenment established pillars in his soul, countering the prejudices of the peninsulares and supporting the truths he had already known in his heart. His experience on the open range of equality and respect, which, to him, seemed heaven-like, was real and was affirmed by the greatest intellects of the Age. His intellect, heart, and conscience grew, merging into a single clear outlook. Morelos matured. He accelerated his education to conclusion, earning high marks for scholastics, and acclaim for ceremony, singing the liturgy after the manner of the priests of old.

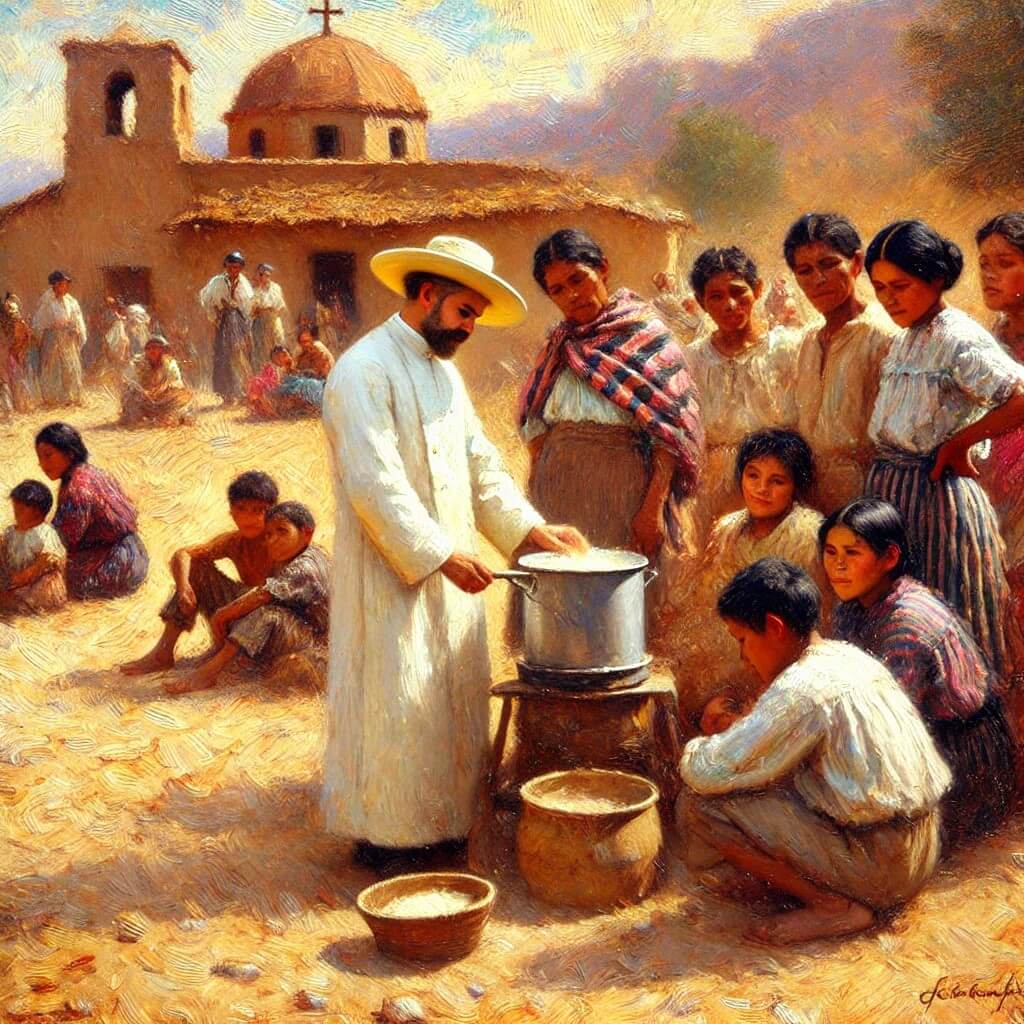

Chapter 5. The Priest

A generation before, Juana Maria’s grandfather, Jose Maria’s great-grandfather, held some prominence in a local Catholic parish and established a patrimony for an heir. Juana Maria lobbied hard to claim this for her son while he completed his education. Upon graduation, the Church offered a position to Jose Maria. The position represented a significant promotion for so recent a graduate, in recognition of his talents, but it came with a difficulty. The location was notoriously hard and with little prestige. Sources indicate his mother opposed the position, at least in part, due to its harsh conditions. Valladolid had been the family home and the place of his education and was known as The Garden of the Viceroyalty of New Spain; whereas the assignment was in Tierra Caliente, an impoverished desert region in the South. Some sources suggest the poor assignment was due to Jose Maria’s mixed ethnicity.

We do know that Jose Maria accepted the position in January 1798, that the family moved to Churumuco, Tierra Caliente, in February 1798, that the mother became ill in the Summer of the same year, and was sent away to a better town for treatment, and, in January 1799, just one year since the move, she died, without Jose Maria by her side, unexpectedly, and alone.

Chapter 6. Tierra Caliente

Tierra Caliente was a parish with about 3000 Indios, spread among a hundred towns and two poor churches. Jose Maria, in performance of the duties of the church, would have spent many hours in the saddle traveling from town to town. He’d observe the land with the eye of a vaquero, learning its seasons and its ways, its high grounds, gullies, and quicksands. And as he rode, he’d sing, singing to prepare epistles for his parishioners, singing as the old priests sang, singing as the vaqueros sang to calm the herd, singing, as an attempt to calm his own soul.

Hot tears wetting the hot saddle leather beneath Jose Maria would not have surprised anyone who really knew him. But a watching stranger might be forgiven their surprise at the image of this desert rider, dressed like a padre, riding like a vaquero, whip, and rope lying easy at his side, singing, weeping.

One imagines the bitterness, just when everything was going so well with the education and then the job offer, and the regret, his mother having advised him against the move, but he did it anyway, and now, she was gone.

It’s not hard to imagine a sadness as broad as the desert and as dry, through which he rode daily on horseback. There he was, without father, without mother, a priest to the Indios, in the backside of the desert.

And there he remained, unknown, riding the circuit in the heat of Tierra Caliente, baking in the desert, riding that same circuit year after year, wondering about the circuit of his life, the experiences of his life baking into him, the lessons of life baking into him, the teachings of the enlightenment baking into him, the bitterness of the Indios baking into him, baking, baking, baking, until, one day, his baking was done, and the bell was rung.

Chapter 7. The Bells of Dolores

The bells were rung with new meaning in Dolores on the morning of September 16, 1810. Hidalgo addressed the people gathered to the church bells. The message, though unrecorded, is universally acknowledged as the event giving birth to the Independence of Mexico. There was hope in the air and the news flew like a golden eagle throughout the land; and, soon enough, reached Tierra Caliente where Morelos heard and looked up.

Chapter 8. The Commission

Jose Maria Morelos emerged from the desert about three weeks after the revolution began to offer his services as a chaplain in the army to his former teacher, Hidalgo. There perhaps was never a man more unexpectedly equipped, nor, more fully ready, as was this man, for the task he was about to receive. The two had wine and the conversation began, the pupil asking his teacher, “What are you doing? They told me to announce your excommunication.” With a slight laugh and head shake, Hidalgo replies, “I am doing exactly what I told you we would do those many years ago. I have not changed, and the world has not changed, so, now, we change the world.” The next day, they traveled to the next town together, and, talking more, Jose Maria Morelos asks, “What would you have me to do?” Hidalgo replied, “Go South, Raise an army, March on Acapulco. I will continue to the gates of the capital. We shall meet afterwards. And if we die, we die for righteousness.”

The qualifications necessary to personally raise an army, to train an army, and to lead an army, into battle, successfully, are extraordinarily rare. Nevertheless, that is exactly what Morelos did. He raised an army, and became their leader; and, within a month he had won his first battle. Thereafter, day by day, people rallied to him, and he trained them, and he led them. Farmers, who knew him from the regions he had pastored, came to him to join the cause. To them, he said, “An army needs to eat as well as fight. You are equal warriors by raising the food upon which your fighters fight. Go back to your farms, and there fight for your brethren and for your country.” In the first year of his commission, Morelos fought and won twenty-two straight victories, destroying three separate royalist armies along the way. We have this excerpt from the letter he wrote to the Spanish Viceroy at the time: “On the fourth day of the present month I have taken possession of the town of Cuernavaca, (I warn you), do not send troops or orders, because the troops will be defeated, and the orders disobeyed.” He continued, commending his personally trained army, “These troops, in whatever number they attack, don’t leave the action until they are victorious.“

Chapter 9. The Sentiments of a Nation

The responsibilities laid upon Morelos grew yet more, with Hidalgo’s capture and execution in 1811. In 1813 Morelos called upon the nation to convene a Congress to draft a constitution for the incipient republic. There he presented what he entitled, The Sentiments of a Nation, a document in 23 points expressing his vision for the emerging independent society. “America is free and independent of Spain and all other nations, governments, or monarchies,” it stated. The country prohibits “slavery forever, as the distinction of caste, being all equal and only vice and virtue distinguish an American from the other.” “Sovereignty emanates from the people and is placed in a Supreme National American Congress, made up of representatives from the provinces in equal numbers.”

In the Summer of 1815, the muleteer reached out to James Madison, the 4th president of the United States, and, in most elegant terms, sought recognition of Mexico’s independence, concluding with express wishes for the success of “negotiations and treaties which may assure the happiness and the glory of the two American nations.”

Chapter 10. The Sacrifice

That same year, as Winter drew nigh, Morelos was called upon to protect the hunted young Congress in a move to a safer town. Betrayed and ambushed by royalists, Morelos fought a rearguard battle until he could see the Congress escaping; then, giving the command “Every man for himself!“ he effectively offered himself as an unguarded prize to the enemy, saving the Congress, as well as the fighters, to fight another day.

He was captured; he was tried; he was defrocked by the Spaniard Catholic Church, condemned by the Spaniard Court of Law, and sentenced to death. The execution was swift, and death came, as ordered, from above. He was buried in a pauper’s grave in a nearby nondescript church.

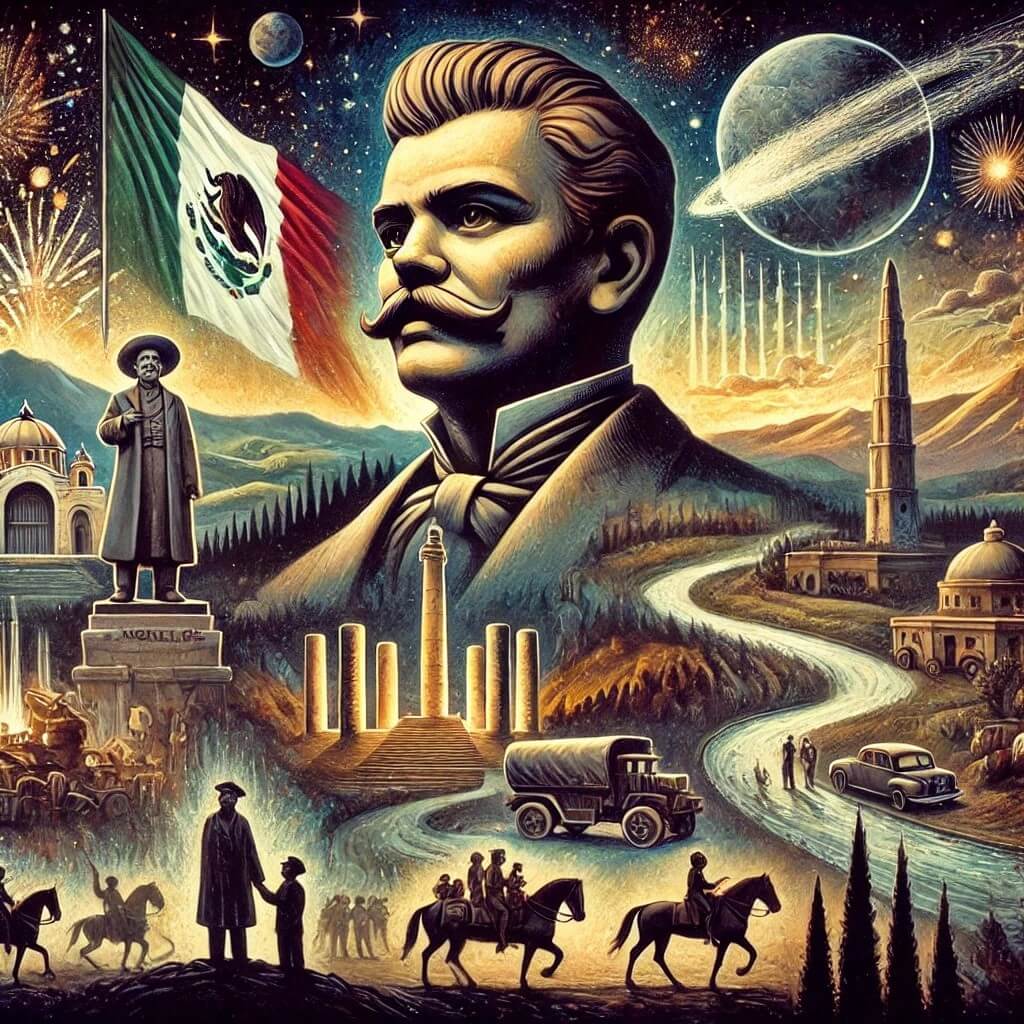

Chapter 11. The Epilogue

The Crown, of course, had hoped that the matter was ended, that Ferdinand VII would reign forever, and the lower classes would remain lower, forever, or for at least another generation. But, it wasn’t the end; not even close. Jose Maria Morelos had entered the theater of nations like a comet in the night sky; and like an unlooked for omen, streaked across the skies for 5 years, leaving an impression upon the psyche of a nation, that would not fade. The war wound its course as wars do, but the memory of Jose Maria seemed fixed. In 1821, Spain finally acknowledged the truth of Mexico’s independence; Jose Maria was remembered, his remains recovered, and removed with ceremony to the Altar of Kings in the Cathedral of Mexico.

The young nation grew, with fortunes ebbing and flowing as they do, but with each generation, it seemed, there were more, and yet more, dedications to the memory of Jose Maria Morelos. The town of Valladolid was renamed Morelia. Cuernavaca, the scene of an early victory, is in the Valley, now called Morelos, which is in the state, now called, Morelos. There were wars and another revolution, and still, the memory of Morelos persisted. In the 1930s, an island in the middle of a lake was dedicated to Morelos, and a 130-foot tall monument raised to his memory and often called the Statue of Liberty of Mexico. There is Morelos stadium, and Morelos parks, and monuments in Los Angeles, California and Yakima, Washington. The presidential plane is named the Jose Maria Morelos, and in 2015, the Morelos 3 joined Morelos 1 and 2 in orbit, as a constellation of technology facilitating the communications of his people into the 21st century. And just now, more than two hundred years later, his story is being read by you.

Chapter 12. The Judgement of His Peers

An alternative scenario for the end of Morelos has been proposed; but, who can really say? Those that were there are no longer with us; and all we have are these monuments, which seem to increase in number and grandeur, with every passing generation. It’s been said the Fates, which had arranged the preparatory stages of Jose Maria’s life, leading up to that incalculable coincidence of the right person, in the right place, at the right time; were quite pleased with their work. Thereafter, they followed his progress avidly, watching and then marveling as he offered himself to his foes, sparing the young congress and their army.

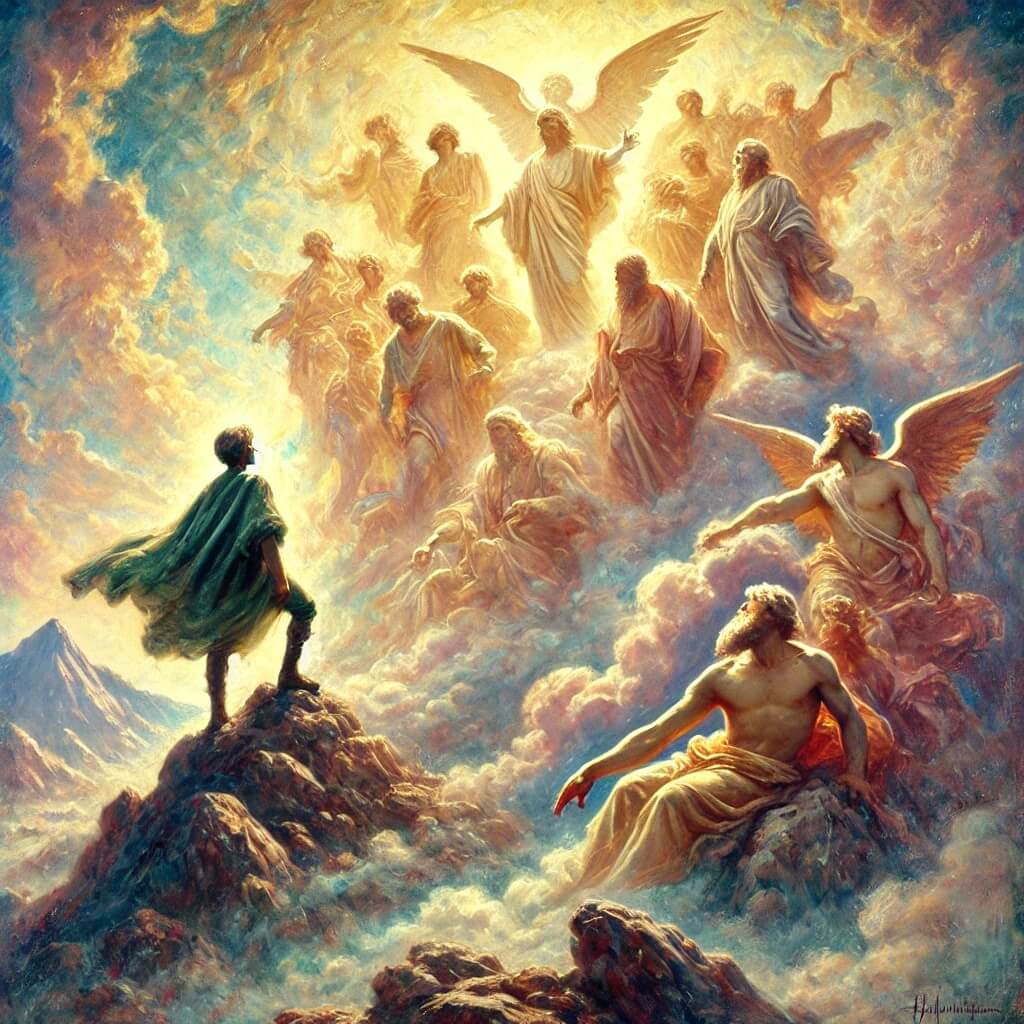

As the courts of men convened to pronounce their judgment, so, were others convening, upon, what some call, mount Olympus. With intense interest, they watched, looking down upon, and into, that little box which men call a courtroom; their eyes fastened upon Jose Maria Morelos, as helpless as a babe in a cradle. Judges and lawyers scowled while gods and angels grinned, glancing at one another, nodding, and watching. They knew the beauty of this scene.

And as the verdict of men became obvious, so it did on Olympus, and with the assent of all, one looked up at Mercury, saying, GO. The next instant, the Winged Messenger, the Swiftest among the gods, the Bearer of the Verdict of the Court of Olympus, Mercury, stood, filling the courtroom but unseen. Jose Maria, looking up, capable of nothing more than hope, locked eyes upon the void, where stood the unseen god, and was strengthened. The judge among men gaveled the sentence of like men, as the message of the gods was uttered, “Come up hither.” And then, shortly thereafter, came Death, who, with great reverence and infinite tenderness, collected Jose Maria Morelos among the Great spirits. And, upon Mount Olympus, they stood as Morelos passed into their midst.

Prefer to listen to the story of Jose Maria Morelos?

Shop products related to the story of Jose Maria Morelos